Ireland's role as a growing financial centre in Europe - Remarks by Deputy Governor Vasileios Madouros

20 November 2024

Speech

Good morning everyone.

It is a pleasure to join you this morning for FIBI’s annual conference.

I know that much of today’s focus will on the outlook for the global banking sector and financial regulation, amid a shifting geo-economic environment.

And that context matters for Ireland, of course: we are a small, highly-globalised economy, with a large, outward-focused financial sector.

But for today’s remarks I thought I would take a step back from near-term economic developments and regulatory initiatives.1

And, instead, take a longer-term perspective, to consider the trends and implications of the evolution of the financial sector in Ireland.

In fact, I think that “evolution” is somewhat of an understatement. Over the past four decades, the Irish financial system has transformed.

From a relatively homogeneous, largely domestically-focused sector, into a growing, diverse and internationally-connected financial centre, in Europe and globally.

Different facets of the changing Irish financial sector

So let me start with some of the key facts. There are several different dimensions to how the Irish financial system has changed over the past few decades.

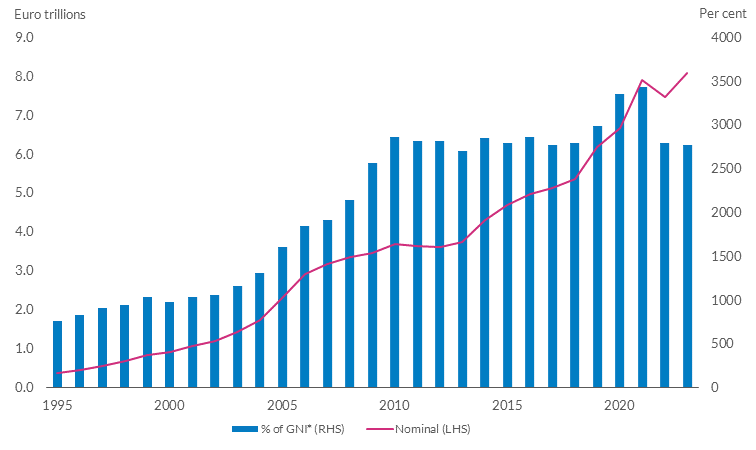

First, the size of the financial system. The Irish financial sector has grown substantially as measured by its total assets, which reached EUR 8.1 trillion in 2023 (Chart 1).

As a share of GNI*, total assets of the sector are now more than 3½ times as large as they were in the mid-1990s.

The growth in the financial sector is also evident in the number of regulated entities operating in the Irish financial system.

That has increased by more than 60% over the past two decades, to more than 12,000 entities.

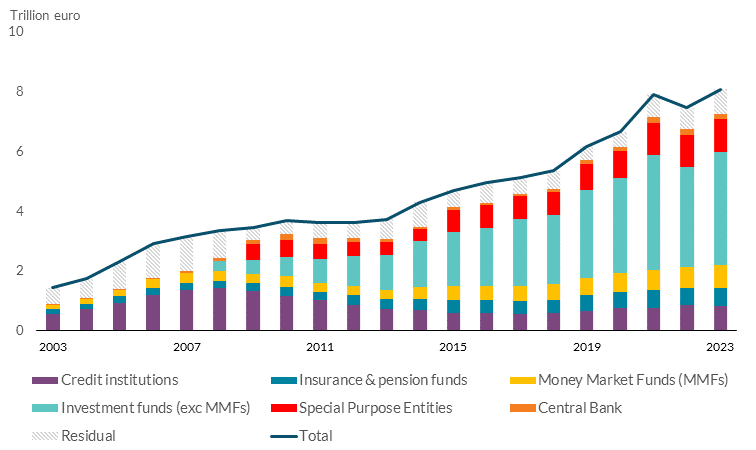

Second, let me turn to the composition of the Irish financial system.

This has also changed markedly over time, with a growing role for non-bank financial intermediation.

In 2003, banks and credit unions accounted for around 40% of total financial sector assets. That share peaked in 2007, but has since fallen to just above 10% (Chart 2). Amid a post-crisis balance sheet contraction, total assets of banks and credit unions have fallen substantially from their peak in 2007.

More recently, the downward trend in the size of the banking sector has started to reverse, driven by the expansion of balance sheets of international banks operating in Ireland.

Chart 1: The size of the financial system has grown substantially in recent years

Chart 2: The non-bank sector has driven the growth in the Irish financial system

Overall, though, the growth in the Irish financial system in recent years has been driven by the non-bank sector, especially investment funds.

Total assets of the funds sector (including MMFs) have increased more than sixfold since 2008, driven by a combination of rising asset valuations as well as significant inflows into the sector.

By 2023, the funds sector accounted for around 55% of the total assets of the Irish financial sector.

Other parts of the non-bank financial sector – such as insurance or special purpose entities – have also seen significant growth over the past decade, but at a slower rate than funds.

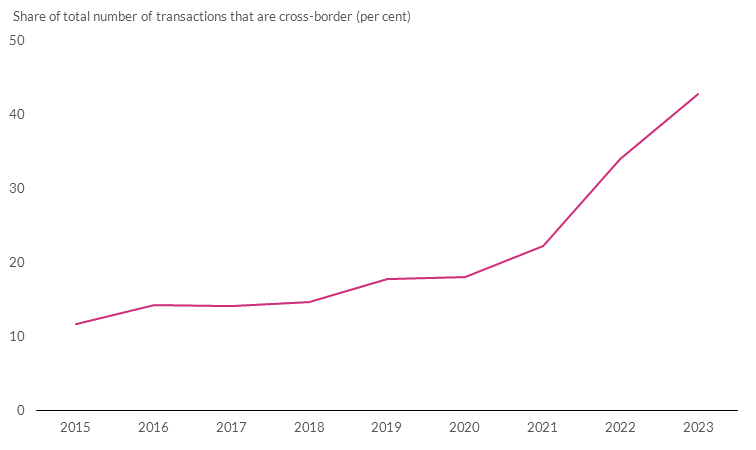

Chart 3: There has been continued growth in cross-border payments transactions

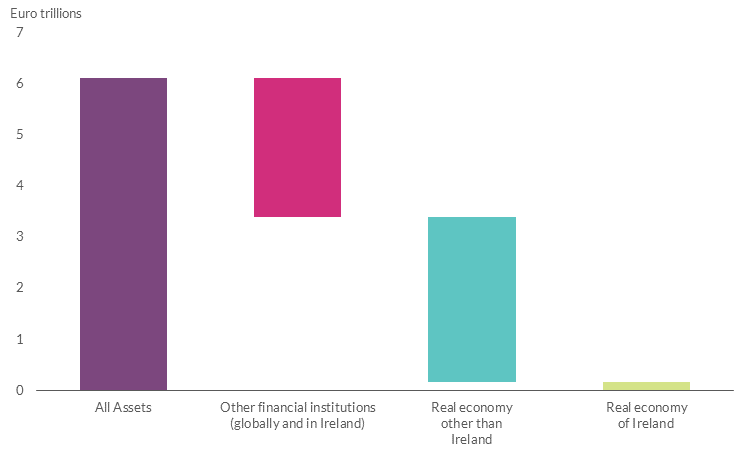

Chart 4: More than 40% of the non-bank sector’s assets are claims on other financial institutions

Third, the international connectedness of the financial system.

That connectedness is not restricted to a particular segment of the financial system.

In banking, Ireland now hosts the European headquarters of a number of G-SIBs and around 60% of the banking system’s assets are claims on non-residents.

In insurance, around 70% of premia written by Irish-regulated insurance firms relate to cross-border business.

In asset management, Ireland has emerged as a global hub for investment fund activity, with the vast majority of assets and liabilities being cross-border in nature.

In terms of payments services, the share of total transactions that are cross-border in nature has risen rapidly recently, to around 40% of total transactions (Chart 3).

Finally, the Irish financial sector has also increased in complexity over time.

The Irish financial sector has not just become increasingly interconnected with the rest of the world.

There have also been growing interconnections within the financial system.

For example, more than 40% of non-bank entities’ asset exposures are to other parts of the (domestic or global) financial system (Chart 4). 2

Additional dimensions of the Irish sector’s growing complexity can be seen in the expansion of particular financial service activities.

- The establishment of the European headquarters of global investment banks in Ireland, with a greater focus on wholesale financial activities;

- The fact that Ireland has been a growing European location for international trading venues and more complex trading firms; or

- The emergence of new digital players, such as payment firms or crypto-asset service providers.

Factors shaping the evolution of the financial system

So what led us here?

I can’t do full justice to this question in the time available, of course.

But there are several characteristics of the Irish economy that have made it an attractive destination for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), including financial sector FDI.

Ireland, for example, is a member of the single market and the eurozone. It benefits from a highly-educated workforce and is English-speaking.

The corporate tax regime is competitive and Ireland’s common law system is attractive to businesses, and has typically been associated with greater degrees of financial development.3

There has also been a high degree of consistency, over successive governments, in Ireland’s policy orientation around the development of the international financial services sector.

But, especially over the past 15 years, three additional factors have played an important role.

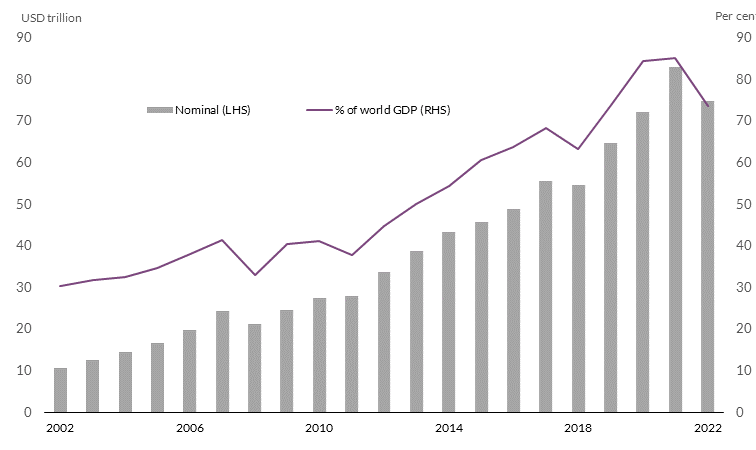

First, the global rise in asset management.

Internationally, the size of the asset management sector has grown rapidly since the global financial crisis.

Total assets under management have risen more than threefold since 2007 in nominal terms, and almost doubled as a share of world GDP (Chart 5).

With Ireland having developed particular expertise in asset management and the investment fund sector, this global expansion of asset management has been a key contributor to the growing market share of the Irish financial sector over the past decade.

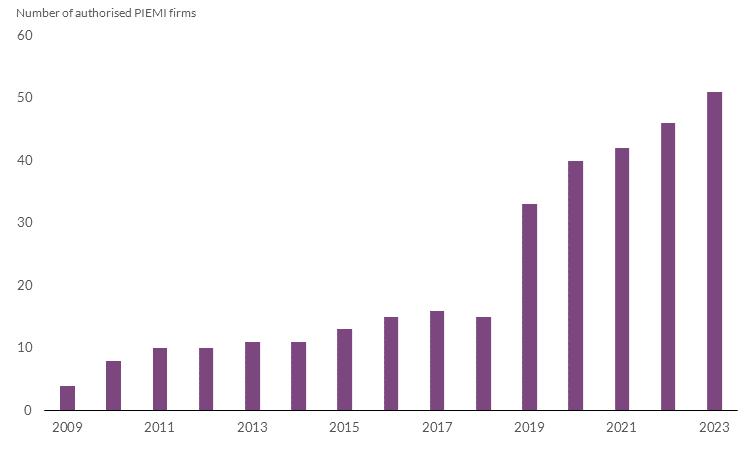

Second, the interaction between technology and finance.

The ongoing digital transformation is affecting every single part of our economy and society. This includes the financial system.

Ireland is both an international financial services center and a hub for global technology firms. Indeed, in recent decades, Ireland has developed expertise in the technology sector.

This combination has created the conditions for the Irish financial sector to gain from increased digitisation of finance.

We see that, for example, in the expansion of fintech companies based in Ireland in recent years, especially in the area of payments (Chart 6).

Chart 5: The asset management sector globally has grown rapidly

Chart 6: The number of PIEMI firms authorised in Ireland has grown rapidly

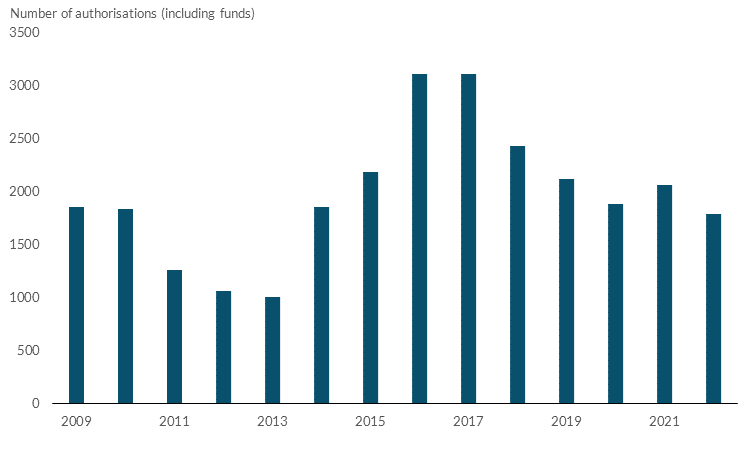

Third, the reshaping of Europe’s financial sector following the UK’s decision to leave the EU.

Following the UK’s decision to withdraw from the EU, Ireland saw a significant increase in authorisations of entities that wanted to maintain access to the Single Market (Chart 7).

The post-Brexit financial landscape in Europe is still evolving, but an important role for specialised financial centres is likely to remain into the future.

Even in the US, despite the prominence of New York, there are several financial centres, with particular areas of specialisation.

Examples include San Francisco’s leading position in venture capital, Chicago’s specialisation in derivatives and commodities trading, or the important role that Boston plays in asset management.

That evolution of Ireland into a financial centre in Europe was not an inevitable outcome.

If we wind the clock back to the 1980s, at the inception of the international financial services sector in Ireland, many were sceptical of its potential prospects.4

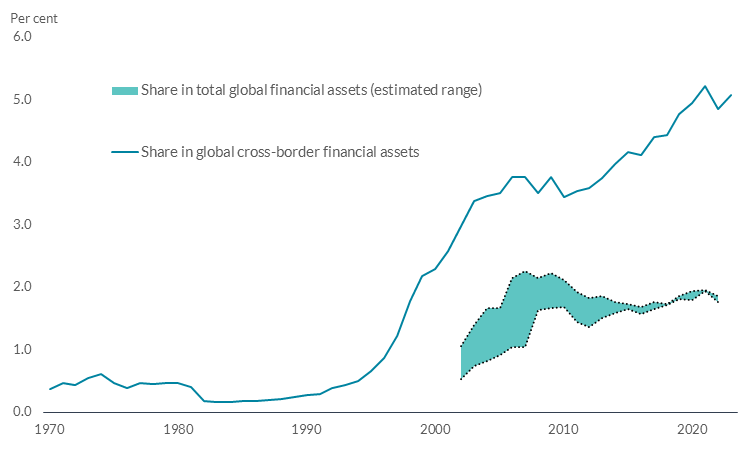

Yet Ireland has now developed expertise and specialisation in cross-border financial services.

And this has been evident in the growing market share of the Irish financial sector.

Over recent decades, the Irish financial sector has been intermediating a growing share of global capital (Chart 8).

For example, Ireland’s share of total cross-border financial assets globally (excluding FDI assets) has risen from less than 0.5% in the early 1990s to around 5% in 2023.

Chart 7: The number of authorisations increased following the UK’s referendum

Chart 8: The market share of the Irish financial sector has grown substantially

The contribution of Ireland’s financial sector to the broader economy

So how should we think about the implications of Ireland’s transformation into a financial centre for the broader economy?

Clearly, the internationally-oriented financial sector already brings several benefits. These are typically thought of – and measured – in terms of domestic economic activity or jobs.

But a broader lens to think about the contribution of the sector is through the core functions that the financial system performs.

For example, the allocation of savings into productive investments, the provision of payment services or the insurance of risk.

Through the provision of such vital services, the internationally-oriented Irish financial system is already supporting the broader European (and global) economy.

Ireland effectively allocates a higher-than-average share of its national resources into finance, and has developed into a key exporter of financial services.5

Looking ahead, and given the make-up of the financial sector in Ireland, it has an important role to play in the further integration and deepening of capital markets in Europe.

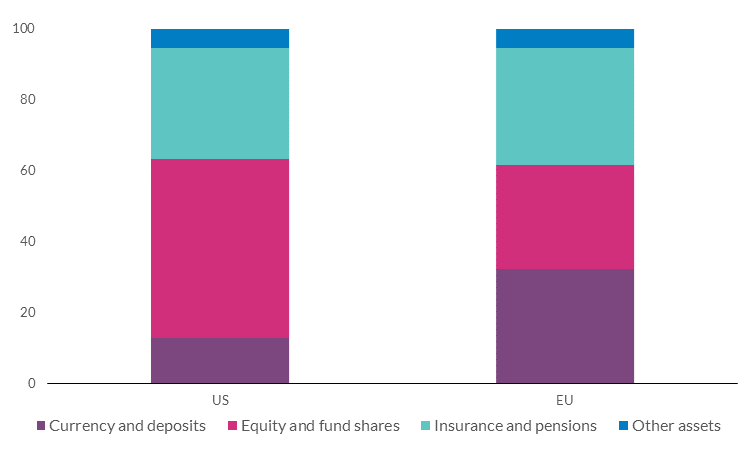

As you know, compared to other developed economies, the EU’s financial markets are more reliant on banks, with a smaller role for market-based finance.

Similarly, capital markets participation by households in the EU also remains lower than in the US (Chart 9).

Making full use of Europe’s capital markets is key to enhancing Europe’s productivity, and to manage the green and digital transitions, amid a shifting geopolitical landscape.

Ireland is already a centre for financial intermediation that specialises in certain activities that are central to the functioning of capital markets.

Take, for example, the large investment fund sector, which is a key intermediary in European capital markets.

Or global banks operating from Dublin, with significant wholesale operations, supporting capital markets activity.

Or Ireland’s important role within Europe for the issuance of securitisation products, a market which the EU is seeking to revive.

In that context, the Irish financial sector is well placed to support key elements of CMU, and can play an important role in delivering deeper and more integrated capital markets in Europe.

And that ultimately matters for Ireland itself. Because our economic fortunes are now inextricably linked with those of our EU neighbours.

Another channel through which the international financial sector can benefit the economy is through the provision of services domestically.

That can strengthen choice and enhance competition, with benefits for domestic consumers and businesses.

Yet, the original inception of the international financial services sector in the 1980s did not consider such a role.

Even today, the links between Ireland’s international financial services sector and the domestic economy remain relatively limited.

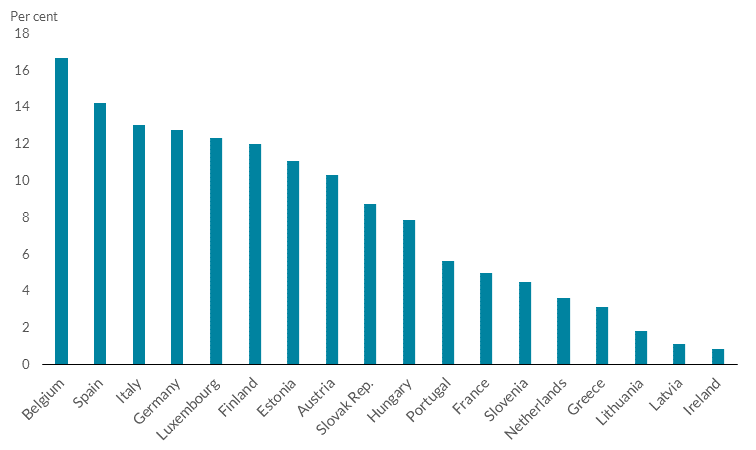

For example, although Ireland hosts one of the world’s largest hubs for investment funds, the share of fund shares in Irish household’s portfolios is low by European standards (Chart 10).

Similarly, with the exception of property-related activity, there are limited financing links between the funds sector and domestic companies.6

In the area of payments, although Ireland is host to a growing and innovative fintech sector specialising in payments, many of the benefits of technology in relation to payments for domestic consumers and the broader economy remain untapped.7

For example, open banking and account-to-account payments are still not widespread domestically.

Chart 9: EU households have a greater share of financial assets in deposits than US ones

Chart 10: Irish households have a low share of total financial assets in investment funds

So there is an opportunity to strengthen the benefits that the international financial sector offers, through increased provision of certain services to the domestic economy.

Recent policy initiatives can support such an outcome.

For example, in relation to household savings, the Department of Finance’s Funds Review focused on the importance of building an investment culture amongst domestic households.8

And it made recommendations to help grow retail participation in capital markets, complementing EU initiatives under the EU’s Retail Investment Strategy.

This could result in stronger links between the large investment fund sector operating in Ireland and the domestic economy.

Similarly, in relation to payments, the Department of Finance’s new National Payments Strategy is seeking to identify and address barriers to the full adoption of open banking and deliver greater choice for consumers and business to ‘pay by account’.9

Ireland’s growing fintech sector, specialising in payments, could make an important contribution towards achieving that outcome.

Regulating a globally-connected financial system

Of course, these economic benefits – for Europe and for Ireland – can only be realised if finance is resilient.

Indeed, if that is not the case, the benefits can turn into costs.

And, ultimately, hosting a global financial centre entails international responsibilities.

Because finance is central to economic activity and the financial wellbeing of citizens.

And the presence of frictions and market failures in finance means that privately-optimal decisions by financial institutions do not necessarily align with socially-optimal outcomes.

This is why – at a global level – finance is a regulated activity.

So jurisdictions that host global financial centres have a responsibility to ensure that the domestic financial system does not become a source of shocks to other economies.

There are different dimensions to achieving that outcome.

First, effective implementation of globally-agreed standards.

This is a bedrock of a resilient global financial system and key to the sustainable success of financial centres, including Ireland.

Divergences in regulatory standards can lead to fragmentation of global finance, contribute to the build-up of vulnerabilities and undermine the flow of capital across borders.

This can have particular implications for jurisdictions that specialise in the exports of financial centres.

Within the EU single market, an increasingly common rulebook for finance is a key enabler for the flow of capital across countries.

And, as a globally-connected financial centre, it is critical that Ireland advocates for the EU to implement globally-agreed reforms faithfully.

This is particularly relevant now, as we are seeing waning appetite globally for the implementation of reforms, such as the finalisation of Basel III.

Second, shaping the development of robust global standards.

This is also an important responsibility of global financial centres.

As the financial system is constantly evolving, the regulatory framework can remain static. To be effective, it needs to be able to adapt to the changing environment.

Much of the innovation in finance tends to occur in financial centres.

So an important responsibility of authorities overseeing financial centres is to shape the development of global standards, ensuring they remain fit for purpose.

That is why Irish authorities actively participate in the European policy-making process on financial services.

The Irish financial sector’s specialisation in non-bank finance is an example where we have also sought to take such an approach at a global level.

Strengthening resilience of non-bank financial intermediation has been a key priority of the Financial Stability Board in recent years.10

The Central Bank of Ireland has engaged actively with international colleagues to strengthen the regulatory framework for investment funds, including from a financial stability lens.

Again, though, it is important that these agreed global reforms are now implemented in Europe.11

Finally, effective oversight, supervision and crisis management arrangements.

This, of course, is at the heart of our own mandate at the Central Bank of Ireland.

For a financial centre it requires, among others, particularly close co-operation with international counterparts.

That co-operation can take different forms, depending on the circumstances.

It can mean common assessment of risks, sharing of data and information, developing common approaches to risk mitigation, or co-ordinating to respond to the crystallisation of risks.

Within the EU, this is now enabled by – and indeed embedded within – the European System of Financial Supervision (ESFS).

This aims to ensure consistent and appropriate financial supervision throughout the EU – and it is a bedrock of the single market for financial services in Europe.

An integrated approach to supervision by relevant authorities in Europe is increasingly part of our DNA.

For an internationally-oriented financial centre, close co-operation with authorities globally is also critical.

The approach the Central Bank took during the Gilt market disruption – and the subsequent introduction of measures for LDI funds – was an example of such co-operation.

During the Gilt market disruption in the autumn of 2022, close co-operation with UK and European authorities – in terms of information sharing and supervisory engagement with relevant asset managers – facilitated the response to the crisis.

The implementation of measures to safeguard resilience of LDI funds in 2023 also required close co-ordination with both EU and UK authorities, to ensure consistent resilience standards were implemented across jurisdictions.12

Overall, a strong regulatory and supervisory framework is a prerequisite for the success of financial centres. Why?

- Because it is critical to ensure that a financial centre does not become a source of shocks, safeguarding global financial stability.

- Because it maximises the benefits the sector brings to the domestic economy, by guarding against vulnerabilities that can amplify the procyclical tendencies of finance.

- And because it builds trust as a place to do business. And, ultimately, trust is a key ingredient that makes jurisdictions an attractive destination for foreign capital.13

Still, history shows that there can be political-economy driven cycles in financial regulation.14 And, globally, we now seem to be at an inflection point in that cycle.

It is in everyone’s interest that these pro-cyclical patterns do not re-emerge.

Of course, we need to constantly evaluate the balance of economy-wide benefits and costs of different regulatory interventions – and we do that.

But it is also critical that we do not forget the core lessons from the past: safeguarding resilience of finance is an essential anchor of long-term sustainable growth in living standards.

Conclusion

Let me conclude.

Over the past four decades, Ireland has transformed into a financial centre in Europe.

That specialisation in cross-border financial services entails several benefits for the broader economy, in Europe and domestically.

Indeed, given the make-up of the sector, it has an important role to play in the further deepening and integration of European capital markets.

And it also has the opportunity to increasingly contribute to the provision of certain services to the domestic economy.

But for these benefits to be realised, resilience in finance is essential.

If that is not the case, the benefits can turn into costs.

Ultimately, it is in the economy’s – and the sector’s – long-term interest that global standards are implemented consistently across jurisdictions, and remain fit for purpose as the financial system evolves.

-

1 I am particularly grateful to Jenny Osborne-Kinch, Patrick Haran, Robert Kelly, Mark Cassidy, Fergal McCann and Simon Sloan for their advice and contributions in putting together these remarks.

2 See also IMF (2022) ‘Ireland: Financial Sector Assessment Program-Technical Note on Financial Interconnectedness of the Market-Based Finance Sector’.

3 See, for example, Beck et al (2003) ‘Law and Finance: Why does legal origin matter?’, Journal of Comparative Economics, Volume 31, Issue 4.

4 Reddan (2008) ‘Ireland’s IFSC: A Story of Global Financial Success’.

5 For example, the share of financial sector employment to total employment in Ireland, at around 4.7%, is the fourth highest in the EU and significantly above the EU average.

6 See Central Bank of Ireland (2023) ‘Market-based Finance Monitor’; Daly et al (2021) ‘Property Funds and the Irish Commercial Real Estate Market’; and Moloney et al (2023) ‘Non-bank lenders to SMEs as a source of financial stability risk – a balance sheet assessment’.

7 See Madouros (2024) ‘The Evolving Payments Landscape in Ireland’.

8 Department of Finance (2024) ‘Funds Sector 2030: A Framework for Open, Resilient and Developing Markets’.

9 Department of Finance (2024) ‘National Payments Strategy’.

10 See, for example, FSB (2024) ‘Enhancing the Resilience of Non-Bank Financial Intermediation: Progress report’.

11 This includes the FSB’s Policy Proposals to Enhance Money Market Fund Resilience and the FSB’s Revised Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Liquidity Mismatch in Open-Ended Funds.

12 Central Bank of Ireland (2023) ‘The Central Bank’s macroprudential policy framework for Irish-authorised GBP-denominated LDI funds’.

13 For example, a recent survey by the Bank of England’s PRA showed that stakeholders care about the reputation of the prudential regulator in providing a stable and predictable prudential regulatory framework that can withstand episodes of financial stress.

14 See, for example, Dagher (2018) ‘Regulatory Cycles: Revisiting the Political Economy of Financial Crises’ IMF Working Paper, WP/18/8.