Behind the Data

Understanding the surge in resident banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018

Author Bernard Kennedy *

January 2022

In this Behind the Data, we show how the increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018 is concentrated in just two financial instruments and three institutions. Although the impact of these loan migrations on domestic credit conditions is limited, there are some implications for supervision and macro prudential policy.

Since 2018Q1, the aggregate balance sheet of credit institutions resident in Ireland has increased by 42 per cent, largely underpinned by developments in the non-resident sector. Developments in banks’ cross-border financial assets and liabilities are an important metric for monitoring international risk sharing (Herzberg and McQuade 2018) as well as internal and external macroeconomic imbalances. However, the activities of foreign-owned Multi-National Enterprises (MNEs) (Fitzgerald 2015) and the presence of a large market-based finance sector (Cima, Killeen and Madouras 2019) can overshadow movements in Ireland’s foreign assets by other entities. Therefore, although the impact on Ireland’s external indicators by the banking sector have been limited so far, it is important to understand why these transactions occurred for financial stability and economic safeguarding reasons.

This Behind the Data uses bank-level data to investigate the increase in cross-border financial assets between 2018Q1 and 2021Q3. The increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018 is concentrated in just two asset classes and three banks with an ultimate parent outside of Ireland. The impulse behind these migrations seems to have been the United Kingdom’s (UK) departure from the European Union (EU) and the need for UK banks to migrate EU assets to their subsidiaries across the EU – including Ireland - in order to continue to serve EU clients.

The Data

The Bank of International Settlements (BIS) Locational Banking Statistics (LBS) report the financial assets and liabilities of internationally active banks against counterparties residing in more than 200 countries every quarter on both a residency and a nationality basis. For Irish resident banks, Central Bank of Ireland collects the data on behalf of the BIS. Banks report their positions to the Central Bank on an unconsolidated, standalone basis including intragroup positions between entities that are part of the same banking group as well as inter-office positions with non-resident branches. Although the LBS responses are reported to the BIS at country level rather individual bank level, the bank-level responses to the LBS allow us to better understand balance sheet movements by resident banks recorded in the Central Bank’s Credit and Banking Statistics when the counterpart is the non-resident sector.

Higher cross-border activity by resident banks since 2018Q1

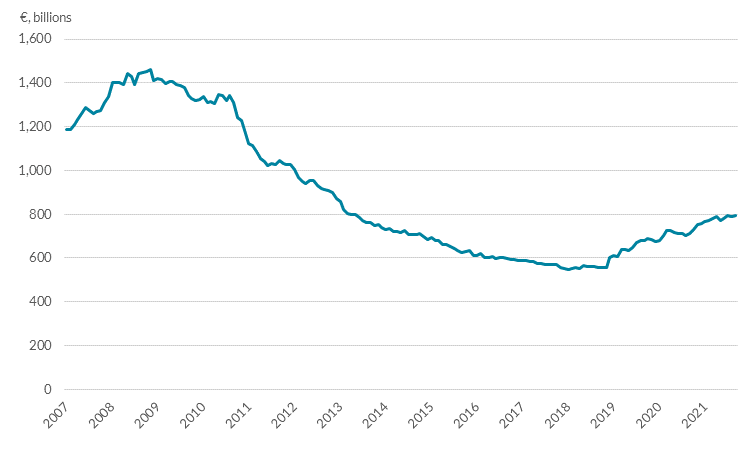

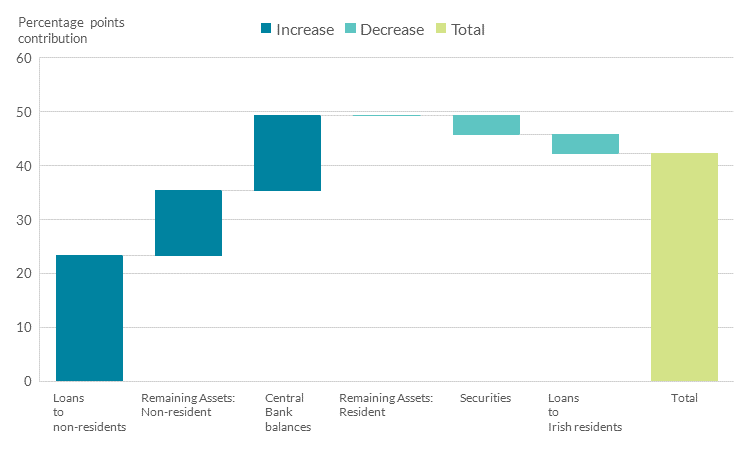

The aggregate balance sheet of credit institutions resident in Ireland decreased from a peak of €1.5 trillion in November 2008 to €551 billion in February 2018 as banks deleveraged their balance sheets following the Global Financial Crisis and several foreign owned banks exited the Irish market (Chart 1). The total increase in credit institutions’ aggregate balance sheet of €235 billion or 42 per cent between 2018Q1 and 2021Q3 represents a big change in direction for the banking sector. Unlike the rapid increase in banks’ balance sheets between 2002 and 2007 which coincided with a corresponding increase in private sector indebtedness, the recent increase since 2018 is driven by positions against non-residents and by central bank balances (Chart 2).

Chart 1: Credit Institutions’ Total Assets: 2007Q1 – 2021Q3.

Source: Central Bank of Ireland and author’s calculations

Chart 2: Contributions to Changes in Credit Institutions' Total Assets: 2018Q1 - 2021Q3

Source: Central Bank of Ireland and author’s calculations.

Note: The chart above shows the total increase in Credit Institutions’ total assets of 42 per cent 2018Q1 – 2021Q3 and the percentage points contribution of different assets.

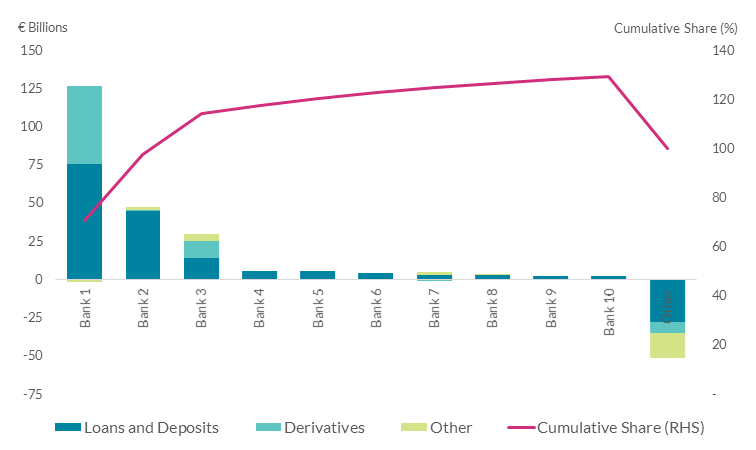

As the main counterpart to the rapid increase in banks’ assets since 2018 is the non-resident sector, it is instructive to study the results of the LBS. The LBS reports banks’ cross-border financial assets and liabilities by geography, sector, and currency of counterparty. According to the LBS, banks’ cross-border financial assets have increased by almost €180 billion since 2018Q1. However, this increase in banks’ cross-border claims is due to the migration of assets from UK banks to their subsidiaries in Ireland rather than any increase in new loans or credit lines that originated from Ireland. Following the UK’s departure from the EU, it has become more challenging for UK resident banks to directly serve EU clients from the EU, and this has resulted in a substantial migration of UK resident banks’ assets to the EU which is discussed in more detail below. Although Irish-resident banks’ foreign currency claims have increased by €58 billion, the increase in cross-border claims is primarily denominated in euro. Furthermore, the increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets is heavily concentrated by instrument and by institution reflecting the small number of banks involved in the migration of assets to Ireland following the UK’s departure from the EU. Just two financial instruments – loans & deposits and derivatives, as well as three banks account for nearly all of the increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018 (Chart 3).

Chart 3: Increase in Banks’ Cross-Border Financial Assets by Institution and Instrument 2018Q1 – 2021Q3

Source: Central Bank of Ireland and author’s calculations

Note: Other encompasses equity and debt securities.

To understand the increase in Irish resident banks’ financial assets since 2018, it’s instructive to look at the categorisation of banks in the LBS. Every bank that participates in the LBS is categorised into one of three categories: ‘Domestic banks’, ‘Foreign branches’, ‘Foreign subsidiaries’. Domestic banks are incorporated in the reporting country or have a controlling parent incorporated in the reporting country whereas foreign branches and foreign subsidiaries have a controlling parent incorporated outside the reporting country. Much of the increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018 is attributable to banks categorised as foreign branches or foreign subsidiaries (Chart 4). Typically the banks in Ireland categorised as foreign branches or foreign subsidiaries primarily serve non-resident clients and have fewer links to Irish indigenous sector. Consequently, the increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets on domestic credit conditions is less apparent.

Chart 4: Increase in Banks’ Cross-border Financial Assets by Bank Type

Source: Central Bank of Ireland and author’s calculations.

Why some banks migrated assets to Ireland

Under existing European rules, receiving a banking licence in one Member State opens the possibility that a credit institution can passport throughout the rest of the European Union without the need to establish a subsidiary in another Member State. When the UK departed the EU, it became a ‘third-country’ with respect to the EU, meaning that UK authorised and incorporated banks were no longer entitled to freely passport into Ireland, or other Member States, as had previously been the case. From the perspective of UK banks they faced additional regulatory barriers to providing cross-border banking and investment services to EU customers. However, the subsidiaries of UK banks that were already authorised and incorporated in one of the EU’s Member States retained their passporting rights. By migrating assets to their EU subsidiaries, UK and international banks were able to retain business lines in the EU and this is discussed in more below. According to New Financial ten large banks and investment banks will end-up relocating £900 billion – or just 10 per cent of total assets in the UK banking systems - to the EU.

Implications for economic and financial stability

As the counterpart to the financial assets that banks migrated to Ireland were mainly non-residents with limited linkages with Irish indigenous enterprises and households, the impact on domestic credit conditions including the pass-through of monetary policy is muted. Furthermore, the immediate implications for credit conditions elsewhere in the EU is also limited as the loans were drawn-down and derivative contracts entered into prior to their migration to Ireland. The impact on Ireland’s external indicators has also been limited so far. The assets that banks have migrated to Ireland since 2018 are captured in two of the indicators that the European Commission monitor as part of the Macroeconomic Imbalance Procedure Scorecard:

- The three-year average of the current account balance as a percentage of GDP

- The change in the Net International Investment Position as a percentage of GDP.

Although banks’ cross-border assets have increased by almost €180 billion since 2018Q1, Ireland’s stock of foreign assets has increased by €2.2 trillion over the same period mainly reflecting developments in the MNE and the funds sector.

Nonetheless, the increase in the size of these entities located in Ireland have implications for supervision and financial stability. The migration of banks’ positions to Ireland has been subject to substantial oversight. For SSM entities, the expectation is that EU products and transactions with EU clients are booked onshore and that risk management capabilities related to these products are also located onshore. Because the volume of assets that migrated from UK and international banks to their Irish subsidiaries was so substantial, some of the asset migrations were treated as an application for a new banking licence. For some banks registered in Ireland that received assets from their UK parent, a new organisation, new risk management and funding structures, as well as significantly higher capital requirements preceded the migration of assets.

These migrations also have had implications for domestic financial stability. During 2019, the migration of banks’ assets from the UK to Ireland 2018 resulted in two additional banks being designated as other systemically important institutions (OSII). This criteria for classifying a bank as systemically important includes indicators of an institution’s size, complexity (including cross-border assets and liabilities), importance and interconnectedness and this framework is outlined by the European Banking Authority.

Conclusion

This Behind the Data uses granular data to investigate the marked increase in cross-border financial assets by banks resident in Ireland from 2018. After the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union in 2016, it was necessary for banks incorporated in the UK to migrate certain EU assets to their subsidiaries across the EU including Ireland to continue to serve EU clients. These migrations were concentrated in loans & deposits and derivatives to non-residents and were underpinned by just three credit institutions. Crucially, these credit institutions have a foreign parent and limited exposure to the Irish indigenous sector.

Although the volume of assets that were migrated to banks resident in Ireland is material, the implications for domestic economic policy and credit conditions and monetary policy are modest given the limited impact on domestic borrowers or depositors. Beyond this, however, there have been implications for supervision and macro prudential policy. Some of the asset migrations were treated as an application for a new banking licence and two additional banks were designated as systemically important institutions. The increase in banks’ cross-border financial assets since 2018 complicates the interpretation of Ireland’s banking statistics. Consequently, the development of a narrower set of banking statistics that distinguish between banks’ whose ultimate parent is incorporated in Ireland and those whose ultimate parent is incorporated abroad might help to guide policymakers.

*Email [email protected] if you have any comments or questions on this note. Comments from Rory McElligott, Maria Woods, Anne Marie Kilkenny, Daniel Martin, Mary Everett, Leo Phelan, Carol Ryan, Richard Fleming, Gordon Barham, Eoin O’Brien and many other colleagues are gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this note are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Central Bank of Ireland or the ESCB.